Disclaimer: The work below was done nearly a year ago. I have no way to test to see if the information is still accurate. I’m guessing it is, but if you’re able to check and see, feel free to let me know if you still get the same results I did.

A while back a friend came to me and they were interested in writing their own mobile app to control their DirecTV DVR. DirecTV already had its own mobile app, but this person wanted to be able to customize some of the behavior. The existing app gave us a good starting point to try and see how to communicate with the DVR.

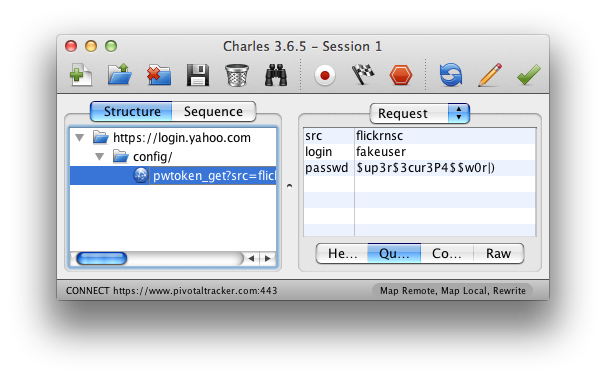

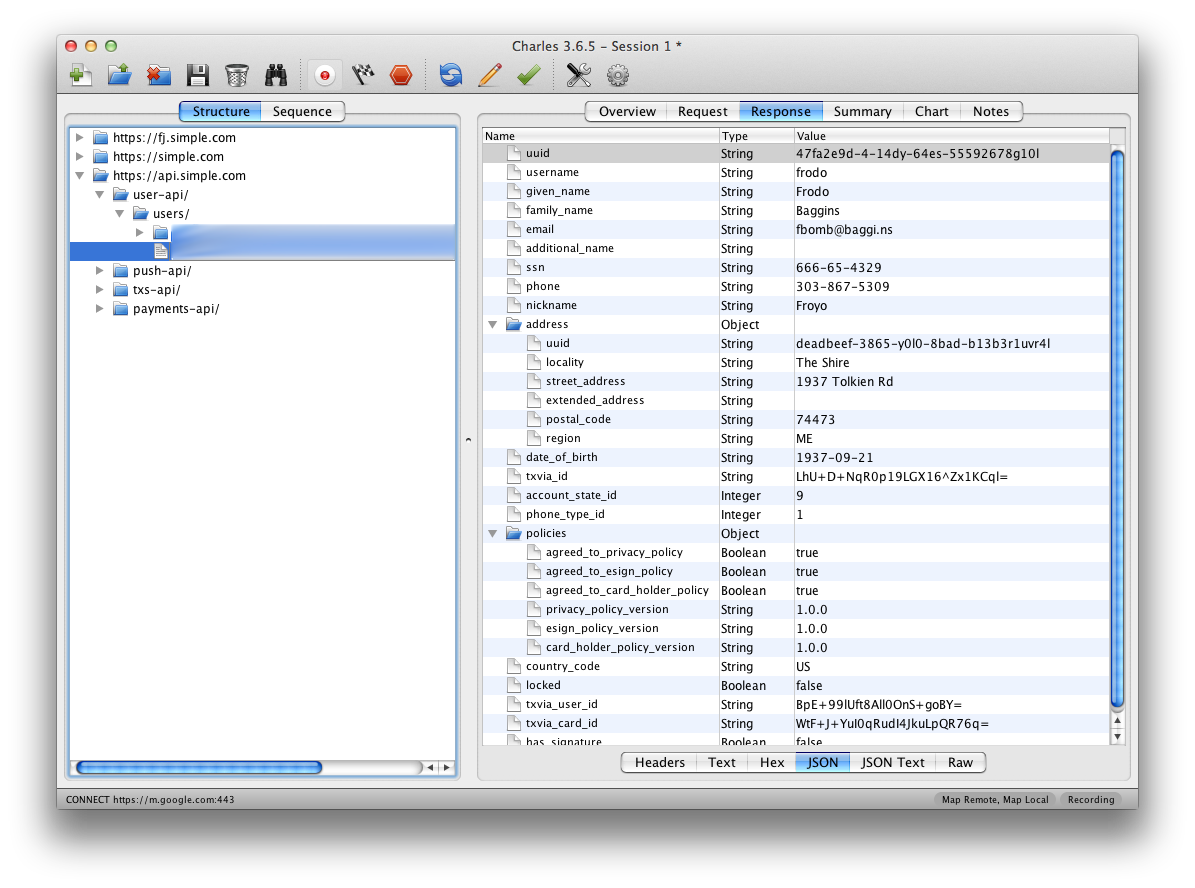

The first place to start was to inspect the local network traffic between the mobile app and DVR. Any proxying tool should work; I went with Charles Proxy. When doing this, we observed an interesting pattern with the traffic. Every time the app sent a request to the server, the server would respond 401 Unauthorized. The app would then send a second request, identical to the first, but this time with an Authorization header. The server would accept this second request and respond. This wouldn’t just happen once at the beginning of a session. Every single request would get a 401 the first time, then would be resent with Authorization headers.

Inspecting the server’s 401 response, it contained a WWW-Authenticate header which included four keys: realm, Qop, Nonce, and Opaque. A quick online search of these keys revealed that the server seemed to be issuing a digest authentication challenge.

A digest authentication challenge is part of digest access authentication; an authentication method that can be used with web servers. The way digest authentication works is that the client and server each know a pre-shared secret (a password). When the server responds to a client with a digest authentication challenge, it’s telling the client how to authenticate itself. The client will generate two strings:

string1 = md5(username:realm:password)

string2 = md5(method:digestURI)

These two strings are then used by the client to generate the authentication response:

response=md5(string1:nonce:nonceCount:cnonce:qop:string2)

If we wanted to talk to this DVR server, we needed to figure out how to authenticate ourselves. In order to authenticate our response we needed a username, realm, password, method, digestURI, nonce, nonceCount, cnonce, and qop.

As mentioned above, the server’s challenge response gave us the realm, qop, and nonce. From the client’s plaintext HTTP response we were also able to obtain the username (c0pi10t), method (GET), and digestURI (path in the requested URL).

This left us still needing the password, nonceCount and cnonce. The cnonce is an arbitrary value chosen by the client (us!) and the nonceCount can just always be 00000001. So really all that was left was the password. The password is the very thing that makes digest authentication secure. The client and server ship with the shared password known to both of them, so they never have to transmit it over the wire.

In order to obtain the password, one option was to try brute force. Digest authentication is used with SIP, for which a couple of brute forcing tools already exist. However, if the password being used is sufficiently complex, brute force is impractical. I took an existing tool and tweaked it a bit to at least start a brute force script while working on some other ideas.

While that ran, I attempted to inspect the application binary itself. Sometimes developers do silly things and leave files around with interesting information, store secret values in insecure places, or don’t bother to obfuscate strings in their binary. Knowing the username gave me a known value to search for. Unfortunately, cursory searches didn’t reveal any clues inside the binary and couldn’t even find a match for our username, so they seemed to at least be doing something to obfuscate the strings in the application binary.

I also decided to start skimming through the digest access authentication RFC (RFC 2069). Looking through the table of contents, one section immediately jumped out: Security Considerations. This section covered some of the benefits that digest access authentication has over basic auth, as well as possible attacks.

Section 3.3 – Man in the Middle – A simple but effective attack would be to replace the Digest challenge with a Basic challenge to spoof the client into revealing their password.

https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2069

The RFC also goes on to explain how this could be combatted. The developers are likely to have coded the client to only respond to digest authentication challenges, and ignore challenges asking for basic auth. The client knows that the server will be using digest authentication and there’s no reason it should accept basic auth as a challenge, especially when an RFC that’s over 20 years old clearly outlines this attack. But it never hurts to try.

Once again using Charles Proxy, when the client tried an unauthenticated request and the server responds with a digest challenge, we modified the response to have a “WWW-Authenticate: Basic†header, indicating to the client that it should authenticate itself with Basic auth (base64 encoded username and password).

When we tried this, much to our surprise, the client actually responded to our spoofed request with Basic Auth. It’s a base64, colon-delimited string, which decoded gives us: c0pi10t:8th5Bre$Wrus. We already had the username (the first part), and now we also had the password.

At this point the door is pretty wide open for writing our own client that can talk to the DirecTV DVR. We have all the pieces we need to authenticate all of our requests to the DVR so that it believes it’s talking to the official DirecTV mobile app. And not just this specific DVR, but any DirecTV DVR that’s capable of working with the mobile app. Based on my (very novice) understanding of digest access authentication, the password must be the same for any DVRs that want to work with the mobile app.