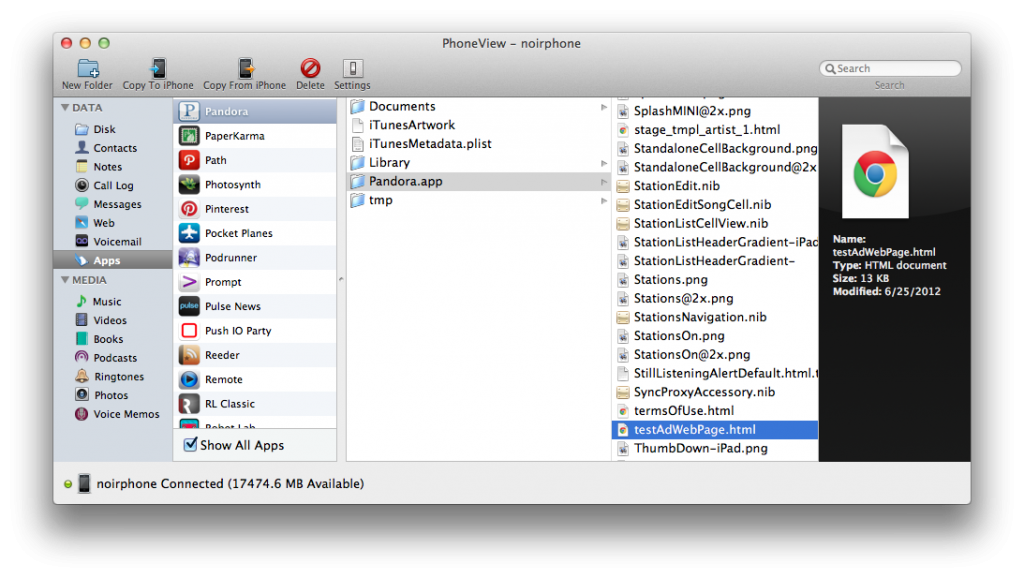

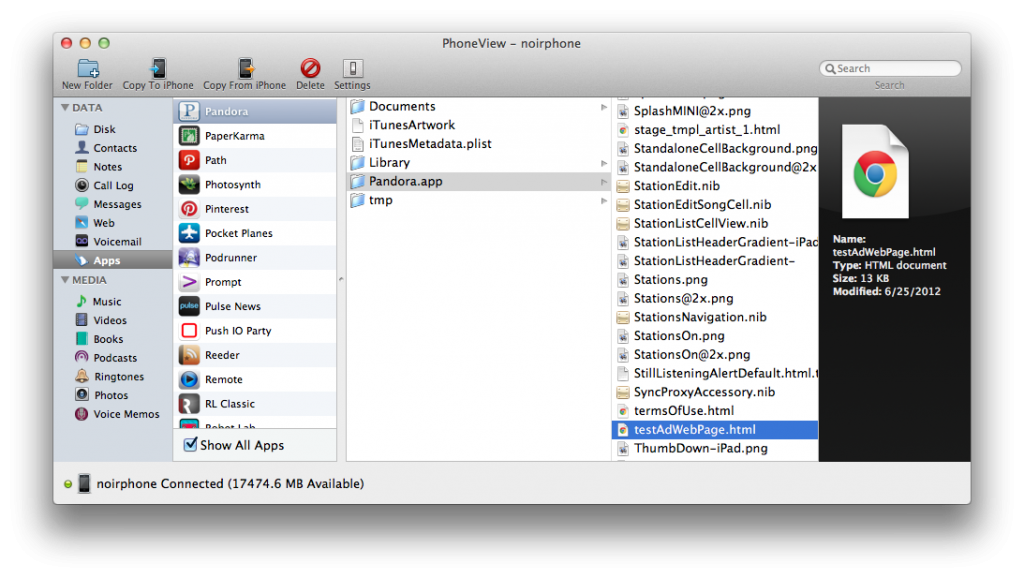

With iOS being a relatively closed system, it’s easy for developers to get lulled into a false sense of security; believing their apps are a black box that users can’t look into. Exploring a few different apps from the App Store, it’s clear that some developers either don’t realize that users can explore their app bundles, or they simply forget this fact. Using a tool like PhoneView or iExplorer, we’re going to peek inside app bundles and look for curious bits that developers may not have intended for others to see.

When exploring app bundles there are generally three different categories of files that are of interest and which developers should be careful with:

- Files that can be manipulated by a user to affect an application

- Sensitive user data

- Sensitive company data

User Manipulated Files

Files in this category are usually some type of data store that hold information about how an application should function, or the current state of the application for a user. To see an example of this, go install

Pocket Planes, run it on your device, then:

- Plug your device into your computer and fire up PhoneView.

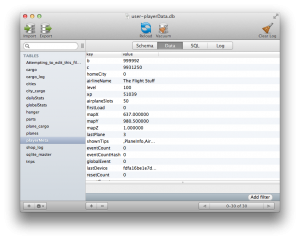

- Navigate to Pocket Planes/Documents/playerData. In there you’ll find the file user-playerData.db.

- Double-click it to save it to your Documents folder. You’ll need an app that can read SQLite 3 database files (my personal preference is Base 2).

- Open user-playerData.db in your preferred SQLite app.

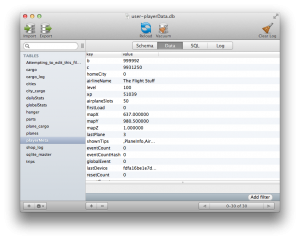

After opening user-playerData.db, you’ll see there are a few different tables. My favorite is “Attempting

toedit

thisfile

maymake

PocketPlanes_unplayable”. Apparently they’re aware that people might attempt to play around in here, so they were kind enough to leave a warning for us to be careful. Take an opportunity here to make a backup of this file, just in case something goes wrong.

With that done, let’s look at another interesting table; playerMeta.  Looking at some of the keys and values in this table, it becomes quickly apparent that this is where all of the player’s game data is stored. It stores how many coins you have (“b”), how many bux you have (“c”), your level, amount of experience, and a few other interesting bits in this table. By now you might see where this is going. You can edit the values in here and change something like your coins to have a value of 9,999,999. Then simply drag this newly updated .db file back onto your device in the same playerData directory you got it from, force quit the application on your device, relaunch, and voilà ! You’re rich. There’s more fun to be found in this app, but I’ll leave that as an exercise to the curious reader.

Looking at some of the keys and values in this table, it becomes quickly apparent that this is where all of the player’s game data is stored. It stores how many coins you have (“b”), how many bux you have (“c”), your level, amount of experience, and a few other interesting bits in this table. By now you might see where this is going. You can edit the values in here and change something like your coins to have a value of 9,999,999. Then simply drag this newly updated .db file back onto your device in the same playerData directory you got it from, force quit the application on your device, relaunch, and voilà ! You’re rich. There’s more fun to be found in this app, but I’ll leave that as an exercise to the curious reader.

So what’s the impact here? We have a free application that presumably makes money from in-app purchases of bux, with which users can buy coins to advance more quickly in the game. But because the value of both the coins and the bux is stored unsecured in a database, any user can go modify these values and avoid having to pay for anything. The impact to developers here is the potential loss of revenue. Additionally in multiplayer games, there’s the possibility for some users to cheat (as once was the case with Hero Academy).

With these types of files, you have a few options as a developer. If you don’t expect the data to change, or any changes could be handled with an app update, then store that data inside of your compiled code. This ensures the data is in the signed binary, out of the user’s reach. If you must update these values regularly, you can implement some kind of a checksum for your application to validate. For an example of this you can look at Temple Run. They store a lot of the user’s data (like coins) in a plain text file, but it’s also checksummed and if the checksum is not correct, the game ignores that data. One more option would be to store these values securely on or validate against a server. Obviously this requires more planning, upkeep and resources than the other options.

Sensitive User Data

It wasn’t that long ago that

Facebook and Dropbox caught some flack for insecurely storing user authentication tokens. Basically the insecure storing of these tokens meant that a malicious user with physical access to somebody else’s device could gain unauthorized access to the victim’s account. Less than ideal. Unfortunately, there is no shortage of other apps out there with similar insecurities.

One such app that I recently came across is My Secret Apps Lite. This app claims it will securely store photos, videos, bookmarks, browsing history, notes and contacts. It also has several mechanisms intended to inform you if somebody tries to gain unauthorized access. It even goes as far as letting you set a decoy pin so that if you’re forced to tell somebody your pin, you can give them the decoy which will show them your decoy data.

One such app that I recently came across is My Secret Apps Lite. This app claims it will securely store photos, videos, bookmarks, browsing history, notes and contacts. It also has several mechanisms intended to inform you if somebody tries to gain unauthorized access. It even goes as far as letting you set a decoy pin so that if you’re forced to tell somebody your pin, you can give them the decoy which will show them your decoy data.

So how does its security hold up? As you may have guessed, not well at all. Not only can all of your “secure” data be accessed in the Library/Application Support directory (bookmarks, history, photos, notes, security log, it’s all in there), but by simply looking at Library/Preferences/my.com.pragmatic.My-Apps-Lite.plist, you can see the pin and decoy pin (if there is one set). In reality, this app provides more novelty than actual security.

Other apps might store most of your sensitive data securely, but still leave some of it unprotected. For instance with Mint, I couldn’t find anything along the lines of account numbers or login credentials, however, it does look like they store your transaction history in a plaintext database. They made the effort to secure other data in the application, so I’m not sure why this data was left in unsecured.

Chrome is another application that stores most of your datas securely, but not all of it.  They made good efforts with decisions like having password encryption turned on by default, but one file that is not stored securely is Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/UIWebViewCookies. If you have one device where a user has logged in to their Google account, then you copy that Default directory of that device to another, after relaunching Chrome, you’ll be able to navigate to any Google website and be logged into the user’s account.

They made good efforts with decisions like having password encryption turned on by default, but one file that is not stored securely is Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/UIWebViewCookies. If you have one device where a user has logged in to their Google account, then you copy that Default directory of that device to another, after relaunching Chrome, you’ll be able to navigate to any Google website and be logged into the user’s account.

You can also glean such details as what websites the user has saved their login info for, as well as the usernames for all of those sites. While they’re not storing your password in plaintext, they’re leaving enough info on the table to make you (or at least me) uncomfortable.

What makes me more uncomfortable is Google’s philosophy regarding mobile security. As you can see in their response to my bug report, their feelings are that you have no expectation of security if you lose your phone. I would agree that if a user loses their phone it’s in their best interest to assume all data has been compromised and respond accordingly, but I also feel developers have a duty to their users to make reasonable efforts at keeping the user’s data secure.

1Password is an example of a application whose developers take their users’ security seriously. Even if an attacker gains full access to your phone and you have 1Password on it, they won’t be able to access any sensitive information from looking in the app bundle because it’s all encrypted. Google made the effort to encrypt passwords, I’m not sure why they wouldn’t bother to secure everything. This is especially troublesome because one of the best features of Chrome is to have all of your data synced across all of your devices. If a company is storing all of my data, I just expect that they’ll make every effort to secure it. Google isn’t alone either. After noticing that a popular Craig’s List app saves the user’s username and password in plaintext, I emailed their support. Over three months later, I haven’t heard anything back from them and they’ve released an update since then, but it didn’t fix this problem. If you’re storing a user’s sensitive data, please ensure you’re doing so responsibly and securely. If you’re a user storing sensitive data in your apps, make sure you check to see how secure that data is.

Sensitive Company Data

Sometimes information goes into your app bundles that is meant to be kept private from others, including your users. One specific example of such information is API tokens for services like Facebook and Twitter. A few months ago I found that eBay’s iPhone app actually had their Twitter and Facebook API tokens stored in plaintext in the app. Such practices are against (at least with Twitter) their terms and conditions. A malicious party could use those tokens to spam or otherwise abuse their APIs and get your valid token revoked, breaking Twitter and Facebook functionality for any of your apps or services that use it. eBay fixed this problem in a recent update and I haven’t yet come across another app doing it, but it’s certainly something to be mindful of. Sometimes you may also come across debug or test files in an app that developers forgot to remove before shipping.

A few months back I was looking for a way to launch into a specific Pandora station using Launch Center (now Launch Center Pro). Looking in Pandora.app at the Info.plist, we can see in the CFBundleURLSchemes section that Pandora has 3 custom URL schemes: pandora, pandorav2, and pandorav3. Unfortunately this doesn’t tell us any of the arguments that you can pass to those URLs to perform more complex tasks, and when I emailed Pandora they were unable to provide any additional information. Fortunately for us a helpful developer left behind a test page in the app bundle. If you look in Pandora.app there is a file called testAdWebPage.html. Opening the file in a text editor, we find exactly what we’re looking for near the end of the page: “pandorav2:/createStation?stationId=” + stId. All you need is the station ID to plug in. You can find this by going to pandora.com and clicking on the station you want an ID for. The station ID will be at the end of the URL. Now with a URL like pandorav2:/createStation?stationId=165870829537384993, you can launch Pandora directly into a specific station. If you have test pages or images or scripts in your project, make sure you clean out anything you don’t want users to see.

As you can see, it’s not hard to find apps that have sensitive data stored with varying levels of insecurity and severity. It’s a good idea to look at your app bundles before shipping to make sure there isn’t anything in there that you don’t want people to see. If your app is storing sensitive user information, make sure you’re securing it; you owe it to your users.

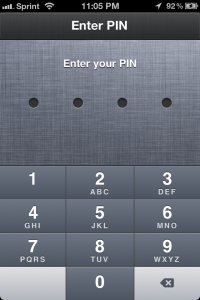

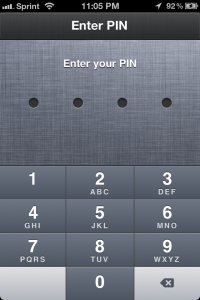

It’s important to note that if you have a passcode set on your device, you won’t be able to use a tool like PhoneView until you enter the passcode. Obviously it’s a good idea to have a passcode set on your device so if a malicious person does gain access to your device, that will provide some type of barrier between them and your data. Sadly not all users choose to use a passcode, and even for those of us that do, it’s not a guarantee. The best thing to do as a developer is assume that security (or your users) will fail, and plan for the worst. You don’t want to be the weakest link in the chain.

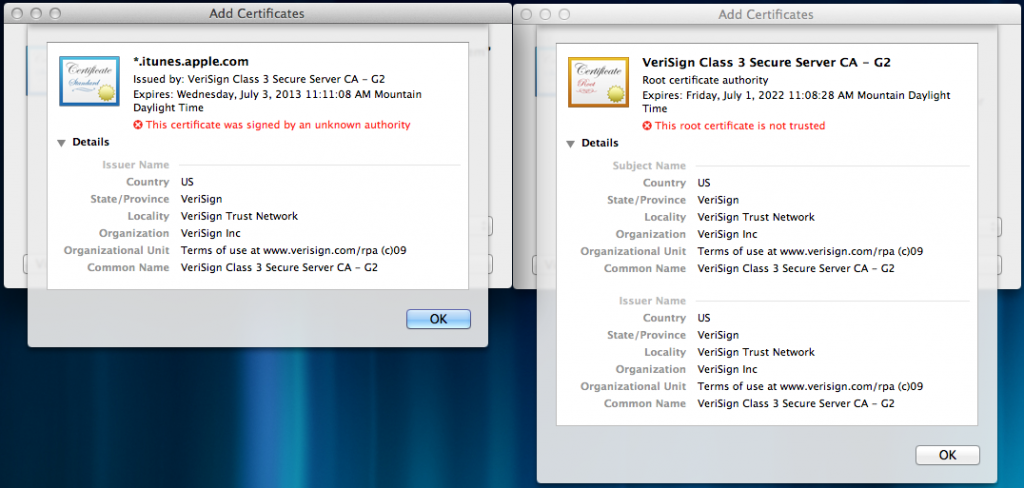

receipts have no uniquely identifying information. The receipts aren’t tied to any particular device or Apple ID. This means that only one person ever has to buy the IAP content, but they can then share that receipt with others who can re-use it to fool apps on their devices into thinking they paid for the content. If Apple were to only fix this part of the problem by having apps check that the receipt belonged to the current device, it would still leave the potential for users to recycle their own receipts over and over. For example, if a user were playing Angry Birds and decided to buy the $0.99 IAP for 20 Space Eagles, they could capture the receipt from the transaction, then re-use it on subsequent transactions for the same in-app purchase. So by paying $0.99 one time, they could acquire unlimited Space Eagle in-app purchases.

receipts have no uniquely identifying information. The receipts aren’t tied to any particular device or Apple ID. This means that only one person ever has to buy the IAP content, but they can then share that receipt with others who can re-use it to fool apps on their devices into thinking they paid for the content. If Apple were to only fix this part of the problem by having apps check that the receipt belonged to the current device, it would still leave the potential for users to recycle their own receipts over and over. For example, if a user were playing Angry Birds and decided to buy the $0.99 IAP for 20 Space Eagles, they could capture the receipt from the transaction, then re-use it on subsequent transactions for the same in-app purchase. So by paying $0.99 one time, they could acquire unlimited Space Eagle in-app purchases.

They made good efforts with decisions like having password encryption turned on by default, but one file that is not stored securely is Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/UIWebViewCookies. If you have one device where a user has logged in to their Google account, then you copy that Default directory of that device to another, after relaunching Chrome, you’ll be able to navigate to any Google website and be logged into the user’s account.

They made good efforts with decisions like having password encryption turned on by default, but one file that is not stored securely is Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/UIWebViewCookies. If you have one device where a user has logged in to their Google account, then you copy that Default directory of that device to another, after relaunching Chrome, you’ll be able to navigate to any Google website and be logged into the user’s account.